This article is about Sepoy Wazir Chand who served in the 20th Punjabis (Duke of Brownlow’s Own) during the First World War and first appeared in the December 2014 issue of The Journal of the Orders and Medals Research Society. I have written guides to help you conduct your own research into soldiers who served in the Indian Army during the First World War which can be viewed by clicking the link below:

Sepoy Wazir Chand 20th Punjabis

Many years ago, I bought a battered victory medal to a sepoy in the 20th Punjabis (Duke of Brownlow’s Own). Knowing the difficulty of researching Indian soldiers, I resigned myself to being unable to add any information to his service. However, I had a starting point: 1250 Sepoy Wazir Chand was listed on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (C.W.G.C.) website as having died on 8 February 1915. [1] Using this date as a starting point, I was able to learn more about Wazir Chand’s last six months and uncover the circumstances of his death.

Wazir Chand’s battered victory medal, one of three he was awarded for service during the First World War. Though it is in poor condition, pockmarked and with the suspension ring missing, it is probable that this medal and a commemoration on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website are the only testaments left to Wazir Chand’s military service.

Wazir Chand was the son of Khushad, from the Kharian district of the Punjab in present-day Pakistan. Kharian is a fertile district situated between the Chenab and Jhelum rivers and had strong links to the Indian Army. [2] The city of Jhelum, where the regiment was garrisoned between January 1909 and February 1914, is located nearby.

When news reached the 20th Punjabis that war had been declared on 4 August, they were quartered in Poona, 1,000 miles to the south of Jhelum near Bombay. The regiment was part of the 16th Indian Infantry Brigade, which itself was part of the 6 Poona Division. On 31 July, orders had been received to rearm with the Lee-Enfield MK III rifle, and now the battalion was preparing for their first active service since the Boxer Rebellion fourteen years before. All leave was cancelled on 12 August and men on furlough as well as reservists were called in.

Initially bound for East Africa as part of Indian Expeditionary Force B (I.E.F) new orders were received on 1 September that assigned them to I.E.F. A to France. However, it would not be until 10 October, after an anxious wait, that the regiment received orders to head for Bombay. The next day, the 20th Punjabis marched to Ghorpadi Railway Station and boarded a train taking them to Bombay, where they embarked on the S.S. Umaria.

The S.S Umaria had been built earlier in the year and, though designed to hold the equivalent of a single battalion of passengers, the 20th Punjabis found themselves sharing with the 117th Mahratta Light Infantry. Leaving the harbour as part of a fleet of three warships and forty-three transports on 16 October, conditions on the ship were poor:

There were no cabins for either British or Indian officers. Wooden compartments had been installed, but there were no fans available. The ship was so crowded that only 50 per cent. of the men could be on deck at one time, so arrangements had to be made to ensure each man getting up for air two or three times a day. [3]

Three days after sailing, the regiment was to watch as the transports carrying I.E.F A sailed off to France without them. For the third time since the war had begun, their destination had changed; instead of France, they were steaming towards Bahrain. Arriving off Bahrain on 23 October, with temperatures averaging over 30°C, morale was low and men ‘openly said they had little enthusiasm for the operations in which we were likely to take part’. [4] But a more serious problem soon became apparent as the Pathan companies began to show unrest at the prospect of fighting against the Ottoman Caliphate and their fellow Sunni Muslims.

The regiment spent the next week practising boat drill and rowing under British coxswains for the proposed landing at Fao, Mesopotamia. Despite early failures, after a few days the men ‘finally acquired enough skill to ensure both their staying in the boat and the boat moving in the desired direction!’ [5] Orders were then received that the 20th Punjabis would be part of the covering party for the landing.

As the S.S. Umaria steamed towards Mesopotamia on 4 November, the regiments on board fortified the ship with goods pillaged from the ships hold, making breastworks from ration boxes, bags of dhal and bales of hay. Britain declared war on Turkey the next day, and that night the S.S. Umaria was anchored with the other transports twenty miles off the strategic port of Fao, gateway to the Shatt al-Arab River on the Persian Gulf.

At 10 am on 6 November, H.M.S. Odin opened fire on the Fao fort, which had been estimated to hold a Turkish garrison of five hundred infantry and eight guns. Fortunately, the Turkish force fled as the landing which the regiment had practised off Bahrain descended into chaos. The plan was for the boats to be towed close to the bank, regroup, then head for the shore:

Unfortunately the Indian Marine officer responsible for putting the boats into position for landing had forgotten that, just at the hour when the operation was to be carried out, the tide turned. The men, never very expert at oarmanship, lost what little skill they had. Some boats landed, some were carried out to sea, some were driven to the Persian shore. [6]

After the boats had been collected, the 20th Punjabis finally landed at three o’clock in front of Fao’s telegraph office. The regiment then marched through a date plantation and bivouacked that night on a mudflat, entering the fort unopposed in the morning. That afternoon they re-embarked on the S.S. Umaria and proceeded up river, being fired on from a Turkish custom house and returning fire with the ship’s Maxim guns.

The next destination for the regiment was Sanniya where they spent an uncomfortable few days with no tents, limited rations and subjected to sudden downpours. A private in the Dorsets described the conditions in the camp after a violent storm, ‘Our kit gave up the ghost & floated away, leaving us soaking wet & no change. We cannot move about for mud, & hungry [sic]’. [7]

On 11 November, four companies of the regiment supported by six guns of the 23rd Peshawar Mountain Battery advanced on a village and date palm half a mile from the camp and cleared out the Turkish forces. The regiment suffered seven casualties, including Major Ducat, mortally wounded. On 15 November, the battalion was part of a reconnaissance by the 16 Brigade which captured a Turkish camp, though most of the regiment was in reserve.

Following up their successes, the 16th Brigade joined the 18th Brigade in a ten mile march to the village of Zainon on 17 November, where reports indicated that a Turkish force was entrenched. On approaching Zain’s fort, the brigades came under shrapnel fire as a sudden deluge began and turned the ground into a quagmire. The 20th Punjabis took up a position on the extreme left of the 16 Brigade, next to the 2nd Dorsets, and supported by the 104th Wellesley’s Rifles and 48th Pioneers. The regiment began to advance at 11 am, sending scouts forward under Captain Saxon, who reported at 11.40 that the enemy was located a thousand yards north-west of the fort. Continuing forward under shrapnel, the battalion began to take rifle-fire and men started to fall in greater numbers. The regiment then exchanged fire with the enemy to allow the Dorsets to try and turn the enemy’s flank and for the artillery to prepare.

By 12.20 pm, a gap had opened up between the 20th Punjabis and the 18th Brigade into which the regiment’s reserves were rushed. As the firing line advanced on a two-hundred yard front, the Turks were suddenly seen to flee en masse from their positions at a distance of seven-hundred yards at 1.30 pm. Opening a heavy small arms fire, the brigade advanced and captured the Turkish camp. In two hours of fighting, the regiment had suffered five British Officers and one Indian Officer wounded, with six other ranks killed and fifty-one wounded. Casualties would have been greater but for the Turkish shrapnel shells bursting too high and inaccurate rifle-fire.

The next objective was Basra, but the regiment would not be part of the advance due to the desertion of six Kambar Khel Afridis from the Pathan companies during the night of 19 November. The commander of the 6th (Poona) Division, Sir Arthur Barrett, asked for the regiment to be withdrawn; however, the decision was taken to keep the regiment in Mesopotamia on account of their reputation. While waiting for the decision, the regiment had embarked on the H.M.T Ekma and was now transferred to the Mejedieh and taken up to Basra, which had been occupied on the 21st.

A busy port, the town of Basra is located on the Shatt al-Arab River and had a population of 60,000 in 1914. The commercial nature of the town was reflected in the eclectic mixture of its inhabitants: Arabs, Jews, Europeans, Assyrians, Armenians, Chaldeans and Persians could all be found wandering the streets and bazaars. A medical officer described the town as ‘a maze of tortuous lanes whose centres were ankle-deep in filth, offal and litter’. [8] The influx of soldiers, combined with a complete lack of sanitation, quickly made conditions ripe for an outbreak of disease, and men started to fall ill with dysentery.

During their time in Basra, the 20th Punjabis were billeted in the Kelsa barracks, a dilapidated and filthy Turkish construction, along with the rest of the 16 Brigade. Taking over policing of the town from the 117th Mahrattas on 6 January 1915, the regiment took to their task in earnest the next day, raiding coffee shops across the city and rounding up ‘some undesirable characters’. [9] The rest of the month was spent searching for arms, laying ambushes, and fighting off attacks on sentries.

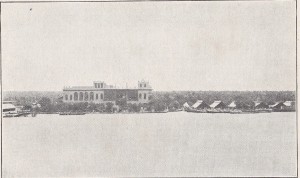

The Sheikh of Muhammed’s Basra Hospital, on the bank of the Shatt al-Arab, where Wazir Chand succumbed to typhoid.

The 28 January is when we can next return to Wazir Chand, as it is on this date that he begins to feel unwell; his symptoms would have begun as a slight fever, nausea, and malaise. The next day, as his symptoms continued, he was admitted into the Sheikh of Muhammed’s Basra Hospital, a former palace on the bank of the Shatt al-Arab, suffering from typhoid. Continuing to deteriorate, Sepoy Chand would have developed a high fever and become prostrate. In the evening of 8 February 1915, the writer of the war diary of the No. 9 Indian General Hospital noted that:

One man of the 20th Punjabis died in hospital this morning of enteric fever [10]. A post mortem revealed extensive and deep ulceration of [the] Peyer’s Patches. He was admitted on the 29 January and his medical officer states he did his duty and did not complain of any illness till the day of previous admission. This man’s regiment is quartered in Busra town where the disease is endemic. [11]

Wazir Chand is remembered on the Basra Memorial, which commemorates members of the Commonwealth forces who died in Mesopotamia and have no known grave. While it has been possible to research Wazir Chand in greater detail than is usual for an Indian sepoy, from the sweltering transport ship, the bungled landing at Fao, to the filth of Basra and his subsequent demise, there are limits. The absence of service records, letters, and local newspaper reports means that researching an Indian soldier tends to focus on the regiment rather than the individual. What was Sepoy Chand’s exact role at Zain; what were his thoughts on the desertions from the Pathan companies; his early life, and so on? Instead, like the vast majority of Indian soldiers, he must remain one of the lost voices of the Great War.

[1] The 20th Punjabis received their first draft of 100 men in October 1915. Combined with this fact, and the date of his death, Wazir Chand was one of the original battalion which left Poona in October 1914.

[2] The C.W.G.C. lists 626 men from the Kharian district who died during the two World Wars.

[3] Anonymous(2003) p5

[4] Ibid p6

[5] Ibid p7

[6] Ibid p9

[7] Townshend(2011) p31

[8] Townshend (2011) p35

[9] War Diary 20th Punjabis WO 95/5121/1

[10] Of the two soldiers from the 20th Punjabis who died in February 1915 only one, Wazir Chand, died on the 8th February.

[11] War Diary No 9 Indian General Hospital. WO 95/5261/6,

References

Anonymous, (2005) Historical Records of The 20th(Duke of Cambridge’s Own) Infantry, Brownlow’s Punjabis, 1908-1922. Uckfield: Naval and Military Press.

Moberly, F. J. (2011) Official History of the Great War Other Theatres: The Campaign in Mesopotamia Volume 1. Uckfield: Naval and Military Press

Townshend, Charles (2011) When God Made Hell: The British Invasion of Mesopotamia and the Creation of Iraq, 1914-1921. London: Faber and Faber Ltd.

War Office WO 95/5121/1, ‘War Diary of 20th Punjabis, from July 1914 to October 1915’. The National Archives

War Office WO 95/5261/6,’War Diary of No.9 Indian General Hospital, from November 1914 to April 1920’. The National Archives.