This article on the 13th Hussars will provide you with an overview of the Regiment’s service during the First World War and help you research those who served with it. This is one of a series of articles on British cavalry regiments. I have also written a series of guides to help you research British soldiers who served during the war:

The 13th Hussars in the First World War

When Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, the 13th Hussars was stationed at Meerut, a city in India, fifty miles northeast of Delhi. The Regiment had landed in India from Britain on 1 October 1904 and had previously been stationed at Secunderabad, in the present day Indian state of Telangana. On 24 October 1914, the 13th Hussars received orders to mobilize for service overseas as part of the 7th Indian Cavalry Brigade of the 2nd Indian Cavalry Division. The Brigade was also known as the Meerut Cavalry Brigade or 7th (Meerut) Cavalry Brigade. On 17 November, the Regiment embarked on board His Majesty’s Transports Dunbar Castle and Risaldar at the Alexandra Docks, Bombay, now Mumbai. The strength of the 13th Hussars was 20 officers, 499 other ranks, 560 horses and a pony. Two days later, the ships sailed for France.

The history of the 13th Hussars during the First World War can be divided into two distinct stages, the first on the Western Front and the second in Mesopotamia, now Iraq. On 14 December, the Regiment landed at Marseilles, France having passed through the Suez Canal on its journey to the Western Front. It then moved into camp at Orléans. By the time the 13th Hussars had arrived in France, a series of trenches had been established from the Swiss border to the Belgium coast. This meant that the Regiment could not be used in its traditional mounted role and there is very little to report during this period. In early January 1915, the 13th Hussars moved into billets at Enquin-les-Mines, a French village thirty miles north-west of Arras. For the next year and a half, the 13th Hussars spent most of its time billeted behind the front line. The Regiment’s exact location can be followed by consulting its war diaries.

While the 13th Hussars spent most of its time behind the front line, in common with other cavalry regiments, it also took turns in the trenches. For anyone wishing to know more about the Regiment’s activities on the Western Front, I’d highly recommend turning to the regimental history The Thirteenth Hussars in the Great War by The Right Hon. Sir H. Mortimer Durand which is discussed below. On the 26 June 1916, the 13th Hussars left France for India and arrived at Bombay on 15 July 1916. However, the Regiment did not stay in India for long as on 19 July, it set sail once more, this time for Mesopotamia. The Regiment landed at Basra on 25 July 1916 where it continued to serve with the 7th Indian Cavalry Brigade. After the fall of Kut-al-Amara in April 1916, the Anglo-Indian force in Mesopotamia was reorganised by Lieutenant-General Sir Stanley Maude during the summer and autumn of 1916. On 13 December, Maude launched his offensive which saw his Anglo-Indian force enter Baghdad on 11 March 1917 after a string of victories. The 13th Hussars played an active role in the advance towards Baghdad and its actions are described in detail in the regimental history.

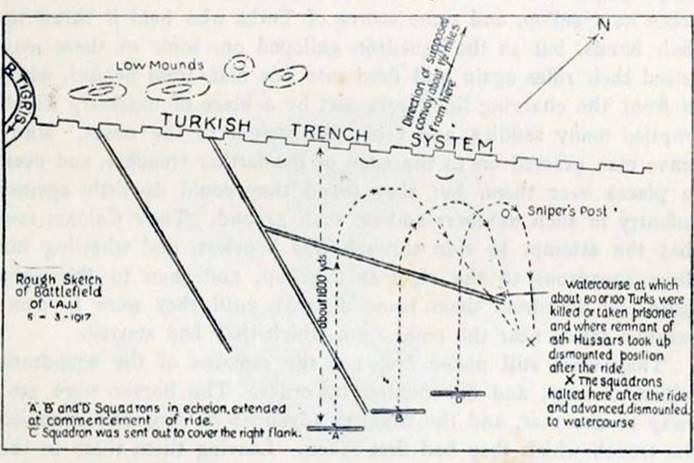

The Regiment was involved in the Fight at Lajj on the 5 March 1917 described in the regimental history as “one of the most memorable in the history of the Thirteenth”. During the battle, the 7th Indian Cavalry Brigade engaged the Turkish rearguard blocking the route to Baghdad. Coming under fire, the 13th Hussars charged and took a watercourse but could not make headway against the strongly held Turkish trench system beyond. The Regiment then dismounted and engaged the Turkish forces until the 6th Brigade was able to outflank the Turks and force their retreat. The 13th Hussars suffered heavy casualties at Lajj of nine officers and seventy-seven other ranks. The map below was taken from the regimental history.

The 13th Hussars was involved in the occupation of Baghdad and for the rest of the year moved frequently. During the summer of 1917, the Regiment occupied a standing camp at Chaldari, nine miles north of Baghdad by the Tigris River. Two squadrons of the 13th Hussars were involved in the capture of Tikrit on 5-6 November 1917, when another cavalry charge was made. The 13th Hussars sustained six killed and twenty-two wounded during the charge. The 13th Hussars moved to Sadieyh after the fall of Tikrit where they encamped until mid-April 1918. The Regiment saw further action at Tuz on 27 April 1918 and during the Battle of Sharqat (23-30 October 1918) where the Regiment made a dismounted charge to capture Turkish guns near Hadraniyah. Both actions are described in detail in the regimental history. After the Armistice with Turkey, the 13th Hussars remained in the vicinity of Mosul, until it returned to Baghdad in January 1919. The Regiment remained in Mesopotamia until March 1919, when it returned to India and subsequently to England where it arrived at Liverpool on 29 April 1919.

Researching a Soldier who Served in the 13th Hussars in the First World War

The first two steps you need to take is to look at my generic guides to researching First World War soldiers and the excellent regimental history The Thirteenth Hussars in the Great War. The guides will help you find service and medal records for soldiers who served in the 13th Hussars. The regimental history contains a roll of all officers and men who served with the Regiment with additional information. Also, I would recommend downloading the two war diaries which I’ve listed below. If you’re researching an officer or other rank who served in India with the Regiment, check the 1911 Delhi Durbar Roll which is available to download for free online.

By combining the 13th Hussars’ war diaries with the regimental history, which is six-hundred pages in length, you’ll have an excellent overview of the service of the Regiment during the First World War. The regimental history also contains dozens of photographs which will be of interest.

Officers: The officers of the 13th Hussars are usually easy to research and if you’re after a photograph look at the regimental history as it contains dozens of portraits of officers. The history also contains lots of quotes from officers and information about those who became casualties or received an honour or award. First, search to see if a service record of an officer is held at the National Archives. There are nine officers of the 13th Hussars listed when the title only is searched among the surviving service records in the National Archives’ catalogue. However, there will be others who are listed under different regiments having been transferred. If an officer served past April 1922 then their service record should still be with the Ministry of Defence. I have written an article about ordering these files on my Second World War website: Ordering a Service Record from the Ministry of Defence. It is a straight forward process which requires two short forms to be filled out.

The photograph of Captain Willoughby Arthur Kennard below was published in The Tatler after he was wounded in 1914. He was wearing the Queen’s South Africa Medal with four clasps. Newspapers are a great resource to use when you’re looking for a photograph or information regarding a casualty or gallantry winner. I have written a page on how to research soldiers using newspaper reports.

Other ranks: The first step is to see if a service record has survived, though if a soldier served past January 1921 it should still be with the Ministry of Defence. I’ve written a guide to ordering these files on my Second World War website Researching WW2. Many service records to those who served in the ranks of the 13th Hussars were destroyed in the Second World War when the warehouse in which they were stored caught fire during the Blitz. Two good sources to check for post-war service are the Royal Tank Corps’ enlistment records 1919-1934 on FindmyPast and the Military Discharge Indexes, 1920-1971 on Ancestry. They are by no means comprehensive and the soldier will have had their First World War regimental number replaced by an army number by 1920/1. The 13th Hussars was mechanized between the two world wars which is why some of its First World War soldiers appear in the Royal Tank Corps’ enlistment records.

If no service record has survived an enlistment date can usually be worked out provided the regimental number is known by looking at surviving service records to soldiers of the Regiment. However, there are two number series for the 13th Hussars so you need to be careful. Pre December 1907, each of the hussar regiments had their own number series which was replaced by a single number block for all regiments from this date. If you know when a soldier was born, you should be able to work out which regimental number is more likely, pre-1907 or post. The regimental history contains a roll of all soldiers who served with the 13th Hussars during the war, including whether they only served in France and if they became a casualty or were awarded a gallantry medal with the date recorded. The history also contains photographs of many other rank casualties and gallantry winners along with quotes from their letters.

To research either an officer or other rank who served with the 13th Hussars, you’ll need to search the records on Ancestry and FindmyPast. Both sites offer a free trial and clicking on the banner below will take you to FindmyPast.

13th Hussars’ Regimental History

The Thirteenth Hussars in the Great War by The Right Hon. Sir H. Mortimer Durand is an excellent book and I cannot recommend it enough. It is packed full of the names of both officers and men and there’s also a handy index. This is one of the most useful regimental histories produced by a unit for the First World War. The history has been reprinted, so it can be bought online or you can read it for free and download the book as a pdf. file by clicking on the link below:

Read The Thirteenth Hussars in the Great War Online

War Diaries of the 13th Hussars

War diaries were written by an officer of a unit and recorded its location and activities. There are two war diaries for the 13th Hussars and both have been digitized by the National Archives. To download each war diary for a small fee click on the blue links below. You may also be interested in the 7th Indian Cavalry Brigade Headquarters’ diaries, with WO 95/1186/1 covering the Western Front and WO 95/5089/1 Mesopotamia.

- Date: 24 October 1914 – 27 June 1916

- 7th Indian Cavalry Brigade, 2nd Indian Cavalry Division

- Reference: WO 95/1186/3

- Notes: A very poor war diary, though August 1915 contains some detailed entries. Most of the entries consist of the word “Billets”. There are no appendices.

- Date: 01 June 1916 – 31 January 1919

- 7th Indian Cavalry Brigade

- Reference: WO 95/5089/4

- Notes: A much better war diary with some very detailed entries, especially for 5 March 1917) and up until May 1917. After May 1917 entries become a lot shorter and include a lot of “encamped”, though April and May 1918 are more detailed. There are a wide variety of appendices including a copy of the Standing Orders of the 7th Cavalry Brigade dated 1 August 1917 and a map of Balad Ruz-Mendali dated 5 October 1917. There is also a detailed account of the 13th Hussars’ attack on 29 October 1918.

Further Sources for the 13th Hussars

If you’d like to learn more about the role of British cavalry in trench warfare on the Western Front I’d recommend Horsemen in No Man’s Land: British Cavalry and Trench Warfare 1914-1918 by David Kenyon.

Extract from The Thirteenth Hussars in the Great War

The extract below was taken from a letter written by Lieutenant George Watson-Smyth which was published in the regimental history. The letter was dated 14 January 1915 and describes his first experience of trench warfare near Festubert:

When I got up to it we were challenged by the post of the Regiment that we were relieving, and then I went up to them. I asked if they were all right. In a very despondent voice he replied, ‘I’ve two men nearly dead with cold: they are both unconscious, and I don’t know how I’ll get them back.’ Just at that moment one more man went over flop. I thought this was a jolly start, as I was going to be there all night and these fellows had been there in the day. We had great trouble to get them out, as the trench was knee-deep in the most holding mud I had ever met. It beat Wadhurst clay by three stone and a distance.

Another difficulty was the fact that the Germans, who were about 600 yards in front, or perhaps a bit more (people are talking all round me, and I keep writing what I hear) kept on sending up ‘Very’ lights and star-shells, which lit up the whole place far better than it was lit up in the daytime. Owing to the snipers, who were lying up all over the place, we had to drop flat as soon as we saw the light going up, and stay there for about a minute after it had gone.

Then I got into the trench, which was bisected by a stream which was just over knee-deep. I put four men one side, and four with myself the near side. I had orders to keep on sniping all night so as to annoy the Germans, so I had one man of each four on sentry for an hour at a time, with orders to shoot about once every five minutes. Of course I could not sleep myself, but I lay down in the wet mud. The trench was over ankle-deep in mud and water, and only just long enough to hold us all.

About midnight it got most damnably cold, and I issued the men milk chocolate, and gave them each a tot of rum from a flask I’d got. The snipers kept on shooting at us, but mostly went over, though a few bullets did hit the trench. One horrid fellow, whom we called Bert, was behind us somewhere, and made me very angry. At 3 A.M. we heard the devil of a battle going on a long way off, machine-firing guns going rapid and a rattle of musketry. This went on for half an hour, and then one or more of our big guns somewhere behind us started firing occasional shots. It made a most colossal row, although it must have been at least half a mile away.

At about 5 A.M. we saw the relief coming up, halted it and saw that it was all right, got out of the trench,… then we went back to the road behind us and walked along it for about 500 yards till we came to the house that the squadron was billeted in. There we got some tea and more rum, and a bit of bully and biscuit, and the men thawed out. The squadron had been in the trenches all night, and had been relieved, as I was, just before dawn. I do not think I ever appreciated a house and a fire so much before as after that twelve hours of water and mud…