This article looks at the Scots Guards during the First World War and will help you to research soldiers who served with the Regiment. This is one of a series of guides I have created to help you research soldiers who served in the British Army. I have also created a guide to researching soldiers of the Scots Guards who served in the Second World War on my other website:

- Guides to Researching Soldiers who Served in the First World War

- Researching Soldiers of the Scots Guards in the Second World War

The Scots Guards in the First World War

Two battalions of the Scots Guards served on the Western Front during the First World War and both suffered heavy casualties. The 1st Battalion was stationed at Aldershot in August 1914 and landed at Havre, France on 14 August 1914. The 1st Battalion initially served with the 1st (Guards) Brigade, 1st Division before it joined the Guards Division on its creation on 25 August 1915. In the Guards Division, the 1st Battalion served in the 2nd Guards Brigade. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission recorded a total of 1486 deaths for the Battalion between August 1914 and November 1918.

The 2nd Battalion Scots Guards was stationed at the Tower of London in August 1914 and served with the 20th Brigade which was part of the 7th Division from September 1914 onwards. The Battalion landed at Zeebrugge, Belgium on 7 October 1914. The 2nd Battalion joined the 3rd (Guards) Brigade, Guards Division on 9 August 1915 and served with this formation for the remainder of the war. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission recorded a total of 1262 deaths for the Battalion between August 1914 and November 1918.

The 3rd (Reserve) Battalion Scots Guards was formed at Chelsea Barracks on 18 August 1914, moved to Esher on 31 August and subsequently to Wellington Barracks, near Buckingham Palace on 2 October 1914. The Battalion remained at Wellington Barracks for the duration of the war training drafts.

Researching Soldiers who Served in the Scots Guards

I’d recommend starting your research by looking for a soldier in the following series of documents digitized by FindmyPast:

- Scots Guards Service Records 1799 – 1939 (over 34,000 sets of records to other ranks)

- Scots Guards Officer Enlistment Registers, 1642-1939

- Scots Guards Enlistment Registers 1799-1939 (other ranks)

Clicking on the banner below will take you to the website and FindmyPast offers a free trial period. The above document sets will provide you with the foundation to research most soldiers in-depth.

Then look through my generic First World War guides, especially those regarding medal records and British Army abbreviations and acronyms. I’d recommend downloading the relevant Battalion’s war diaries (see below) and also getting either a copy of the regimental history: The Scots Guards in the Great War 1914-1918 or Randall Nicol’s excellent two-volume Till The Trumpet Sounds Again.

Researching Officers: A service record is the key document to find which will either be held at the Scots Guards’ Archive or National Archives. There are over 200 Scots Guards officer service records at the National Archives. The Scots Guards Officer Enlistment Registers, 1642-1939 are on FindmyPast and will provide a summary of an officer’s career, promotion dates, decorations, wounds etc. Both the regimental history The Scots Guards in the Great War 1914-1918 (see below) and the war diaries of the Scots Guards contain frequent mentions of officers. Due to the background of officers of the Foot Guards, a newspaper search can produce good results, especially Tatler, and The Sphere for casualties: using newspapers to research soldiers. If you’re researching an officer who served with the 2nd Battalion in 1914-15 then Letters Written from the Front in France Between September 1914 and March 1915 by Sir Edward Hulse is a good resource.

Researching Other Ranks: Start by searching the Scots Guards Service Records 1799 – 1939 and Scots Guards Enlistment Registers 1799-1939 on FindmyPast. A service record is the most important document to find. The enlistment books include a soldier’s age, trade, often where they were born and other biographical information so if you don’t know their regimental number you have enough information to find the correct soldier. You can also look for medal records, search the National Roll of Honour, online newspapers and look at The Times casualty lists. If a service record hasn’t survived and you don’t know which battalion a soldier served with abroad look at their medal roll as it should record either 1SG or 2SG or both, with the number denoting the Battalion. You can then download the relevant war diary below but a service record will record when a soldier served with them.

Private Arthur Douglass, Scots Guards died of wounds at King George Hospital, Stamford Street, London at 7.15 pm on 21 November 1917 and was buried in the Brompton Cemetery, London. Arthur’s service record can be found in Scots Guards Service Records 1799 – 1939. Arthur enlisted into the Scots Guards at Glasgow on 18 February 1915 and spent over a year with the 3rd Battalion before he was posted to the 1st Battalion on 9 August 1916. Arthur was mortally wounded while serving with the 2nd Battalion on 9 October 1917 during the Third Battle of Ypres, better known as the Battle of Passchendaele. Part of Arthur’s medical record survives in his file which recorded that he became paraplegic after a shrapnel ball hit him in the spine. The doctor notes that Arthur was “depressed and takes nourishment badly”. He was one of thousands of soldiers seriously wounded abroad who were invalided back to Britain only to die of their wounds or illness. Many men were still dying in consequence of wounds received in the war decades after it had finished.

War Diaries of the Scots Guards

There are war diaries for both the 1st and 2nd Battalion which have been digitized and are available to download for a small fee from the National Archives’ website. Make sure you get the correct war diary by checking a soldier’s service record or medal roll.

War Diaries of the 1st Battalion Scots Guards

- Date: 04 August 1914 – 03 August 1915

- 1st Brigade, 1st Division

- Reference: WO 95/1263/2

- Notes: While there are some longer entries this isn’t the most detailed war diary when compared to others of the period.

- Date: 04 August 1915 – 31 January 1919

- 2nd (Guards) Brigade, Guards Division

- Reference: WO 95/1219/3

- Notes: A good war diary with a variety of appendices including a report on a raid carried out on the night of 25/26 May 1917.

War Diaries of the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards

- Date: 04 October 1914 – 31 July 1915

- 20th Brigade, 7th Division

- Reference: WO 95/1657/3

- Notes: A very good war diary with detailed entries when the Battalion was in action. There is a report on “Incidents, October 25th and 26th, 1914 resulting in my Capture as a Prisoner of War” by Major The Earl of Stair and another report for the same period by Major Charles Vincent Fox. The latter account is transcribed below. Also, a report by Lieutenant- Colonel Richard Bolton detailing the circumstances which led to his capture. A sketch map of positions east of Kruiseke on 26 October 1914 and an account of the operations of the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards in March 1915.

- Date: 01 August 1915 – 28 February 1919

- 3rd (Guards) Brigade, Guards Division

- Reference: WO 95/1223/4

- Notes: A good war diary with detailed entries for when the Battalion was in action. There is a narrative of operations from 4 – 7 November 1918.

Regimental History of the Scots Guards

The Scots Guards in the Great War 1914-1918 by F. Loraine Petre, Wilfred Ewart and Major-General Sir Cecil Lowther. A good regimental history which contains a number of maps and an index. There is a chapter on the number of casualties suffered (no names) and the number of orders and decorations awarded. The regimental history has been reprinted by the Naval and Military Press.

Further Sources for the Scots Guards

The best book on the Regiment during the war is Randall Nicol’s Till the Trumpet Sounds Again: The Scots Guards 1914-19 in their own Words: Volume 1: ‘Great Shadows’ August 1914 – July 1916 and Volume 2: ‘Vast tragedy’ August 1916 – March 1919. This book is usually on offer at a fraction of its retail price from the Naval and Military Press. There is a two-volume History of the Guards Division in the Great War 1915 – 1918 by Cuthbert Headlam.

A collection of Sir Edward Hulse’s letters were published after his death at Neuve Chappelle in March 1915. Hulse served with the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards and Letters Written from the Front in France Between September 1914 and March 1915 can be viewed for free and downloaded online by clicking on the link below.

Letters Written from the Front in France

Account of Major Charles Vincent Fox’s Capture

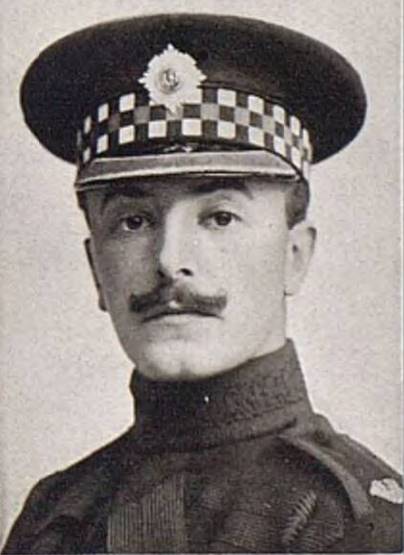

The following account appears as an appendix in the first war diary of the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards. The account was dated 8 January 1918, at Wellington Barracks where Major Charles Vincent Fox was serving with the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion. Major Fox was a career army officer and was educated at Oxford before being commissioned into the Scots Guards in April 1900. He had seen extensive service in Africa, though not in the Boer War. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his actions just prior to his capture. After two failed escape attempts, Major Fox managed to escape and returned to Britain in July 1917 where he was received by the King. He died in 1928.

Sir,

I have the honour to forward herewith a report in brief to replace my long original report.

On the 25th October 1914 my Company was withdrawn from Polygon Wood where the Wiltshire Regiment had been captured, and where F Company, 2nd Battalion Scots Guards had been reduced to Second Lieutenant Gipps and some 60 men. I reached the reserve trenches in rear of the village of Kruisik [Kruiseke] (near Ypres) after dark. At 9 pm, Private Raye, a scout, came in to say that the Germans had broken through our line and were entering the village in strength.

Major The Hon. H. Fraser took this scout to our Brigadier, (Ruggles-Brise) who ordered Major Fraser to retake the lost trenches with two Companies, 2nd Battalion Scots Guards, Right Flank Company under The Earl of Stair, Left Flank Company under my command.

It was a pitch dark night and raining hard. In approaching the village we were forced to halt and allow a large force of Germans to pass us. We retook the lost trenches, captured 204 Germans and 8 Officers, handed these prisoners over, moved by hand a large number of our wounded from houses in the village, who had been prisoners of the Germans all night, and manned the lost trenches.

At daybreak next morning the bombardment began. We were under machine gun and rifle fire from the villages in rear. The Troops on our right were made prisoners at 7 am. We had only one machine gun (worked by Lieutenant Fane Gladwin). This gun and Lieutenant Fane Gladwin were knocked out at 12 noon. At 1:40 pm I had just crawled into my Colonel’s trench, to ask what he was going to do, when I saw one British “Tommy” with his hands up – Germans were coming along the trenches from our right and from the village behind. We had no field of fire to the right owing to a hedge and none to the rear owing to houses. We had had no sleep for five nights, and had shot away all our ammunition.

At the collecting station we numbered 84 of all ranks, Scots Guards, South Staffords, and Border Regiment. Just before the end, I got out of my trench to try to crawl to a house in the rear which was held by a German machine gun. Six men followed me out, four were shot dead, Lance-Corporal Dodd was severely wounded (he has since been discharged), and Private Farrell was wounded. I received two slight wounds myself. I dragged Private Farrell into a trench where I found only one man alive. I was bandaging Private Farrell when a bullet passed through the flesh of my shoulder, killing Private Farrell instantly.

I then crawled into my Colonel’s trench as above related I found the Colonel fighting with a rifle. I asked him what he was going to do. He said, “My orders are to stay in out trenches”. Quicker than I can write it some 20 of our men were standing up surrounded by Germans. A last salvo was fired at our trench; when we put our heads up again, the Germans were standing over us with their rifles. We were prisoners.

I could not keep up with the other prisoners, and a wounded man asked me by name not to leave him. I was trying to carry him [some words are missing from the account in the next paragraph] German bayoneted him. I was making my best pace towards a group of Germans seized me, and stripped me of equipment, money and valuables. The Officer came up my own men to help me back. I was taken along the line of our trenches. I saw no man come out of them alive. In front of Lieutenant Fane Gladwin’s machine gun was a pile of dead Germans, which I estimated at 240. The nearest dead German was lying on the parapet itself, of the gun-pit.

Our orders were to hold on at all costs. I think we obeyed those orders. We fought a superior force to a standstill. We paid all the costs ourselves – three awful years of prison, of insult, of brutality.

These two companies felt that we had more than pulled our weight. We had captured 204 Germans, with 8 Officers. We had held an unsupported trench, when the Wiltshire Regiment had been captured. We had retaken and held for hours, the salient outside Kruisik village. I have a few names I should very much like mentioned for honours in connection with this affair.